War crimes and controversies in warfare are, sadly, a common occurrence. They are often violent, brutal, and despicable, potentially overwhelming the good effort or works being performed during a military operation and changing public opinion, if not splitting it.

The My Lai massacre during the Vietnam War and the Abu Ghraib scandal of the Iraq War assisted in changing the public’s opinion of America’s involvement in the respective conflicts as well as damaging the entire counterinsurgency (COIN) strategy in place while others, like the U.S. occupation of Haiti during the Banana Wars of the 1920s and the No Gun Ri Massacre during the Korean War, have all remained stains upon the U.S. Armed Forces and American foreign policy abroad, being able to be used by enemy governments and forces to discredit a current, internationally beneficial mission.

While most Western individuals are unfamiliar with Canadian military history, they have their own fair share of abuses and issues. None of those has been more internationally publicized and known than the Somalia Affair.

The Somalia Affair

This year marks the thirtieth anniversary of one of the worst scandals in Canadian military history, albeit one that is much forgotten by the international community.

In the 1990s, Somalia became a failed state riddled with famine and various tribal and political clans jockeying for power. In response, the United Nations (UN) sent in a multinational force of peacekeepers to maintain and bring about order while turning the East African nation into a functioning nation-state. Canada was one of those nations that were involved in the effort.

According to The Canadian Encyclopedia, “At the end of the 1980s, Canada was at the height of its reputation as one of the world’s leading peacekeeping nations”, and for over forty years “Canada had contributed 80,000 military personnel to a series of United Nations peacekeeping missions from Congo to Cyprus” becoming a true mainstay amongst the international peacekeeping community.

In late 1992, the Canadian government decided to deploy the “Canadian Airborne Regiment (CAR) and … a reconnaissance squadron from the Royal Canadian Dragoons” to assist in the UN’s peacekeeping mission, continuing their presence in international military operations.

According to J.L. Granatstein and Dean F. Oliver, the director of the Canadian War Museum and the Canadian Museum of Civilization, respectively, writing in the 2013 journal Canadian Military History, “In the early 1990s, the Canadian Forces (CF) had been stretched to the breaking point by budget cuts and force reductions and a continuing string of high-profile and dangerous international security deployments … [the Canadian Airborne Regiment] was the only suitable combat unit not already deployed, recovering from a deployment, or preparing for one”. However, Peter Desbarats, Dean of the University of Western Ontario’s Graduate School of Journalism and a presiding member of the later government committee investigating the affair found that internal discussions were held amongst senior Canadian military officers questioning whether the CAR was suitable enough to be sent abroad on the deployment.

The CAR was sent to “Belet Huen to preserve the peace while allowing food and other items to reach the native population, many of whom were starving”. However, their job was made difficult, given constant attacks from Somali warlords. In response, the senior commanding officer of the Regiment, “Lt.-Col. Carol Mathieu, authorized his men to shoot looters in the legs if they ran from soldiers patrolling the compound”. In contrast, another “senior officer granted permission for thieves to be captured and abused”.

Things culminated in March of 1993, after some three months of Canadian forces being deployed to Somalia. On the 4th of March, Canadian soldiers laid out “food and water as bait near a perimeter fence”, waiting until two Somalis broke through a gap in the fence; upon giving orders to halt and the two Somalis fleeing, Canadian soldiers “shot both in the back”.

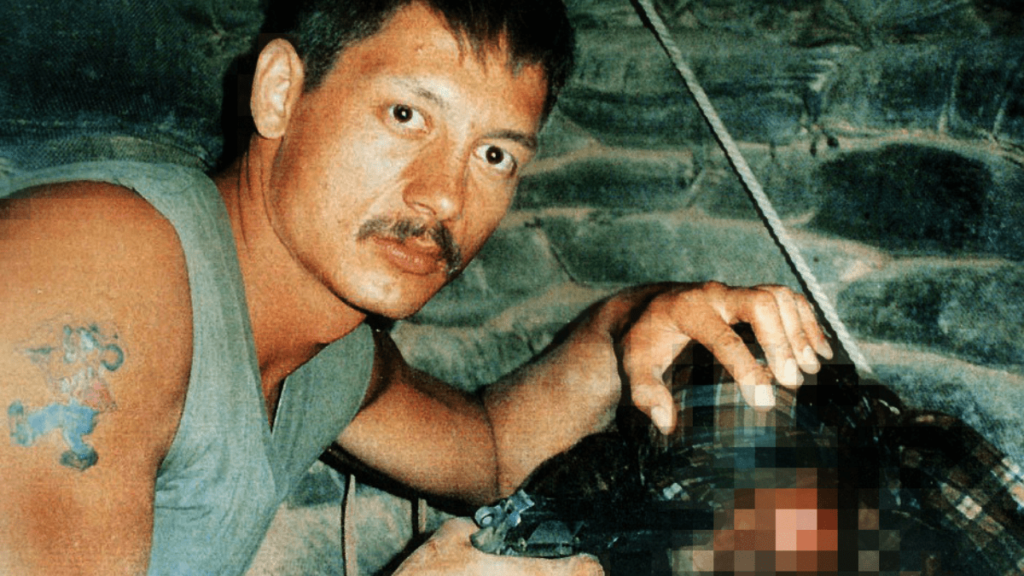

Twelve days later, on 16 March, matters escalated even more. Late at night, “[16-year-old Somali Shidane Abukar Arone] was found hiding in a portable toilet [on base] by [the CAR]” submitting to the Canadian soldiers without resisting arrest, claiming he was searching for a lost child. According to a retrospective by The Toronto Sun, Arone “was tied up and blindfolded then punched, beaten with a metal bar and burned with cigarellos for hours (he was later found to have burns on his penis)” in addition to having been “sodomized by a stick”. This occurred all while the soldiers took “trophy photos” showing the soldiers holding weapons to Arone’s head or shoving a baton in his mouth.

After this, CAR command “was slow to start an investigation into the torture-killing and only did so under pressure from a group of 2 Commando’s sergeants and Private Brown,” and further public attention was only given once Liberal party politicians were conducting their own investigations into certain CAR members’ ties to white supremacy.

Public outcry only came once there was the release of the photographs taken of the incident in November of 1994. According to Granatstein and Oliver, “The resulting firestorm of public criticism all but forced the minister of national defence in the Chrétien government, David Collenette, to order the disbandment of the Canadian Airborne Regiment on 5 March 1995”. According to Vice News, “Two men [Master Corporal Clayton Matchee and Private Kyle Brown] were eventually charged with Arone’s murder and torture”; Matchee attempted suicide and suffered permanent brain damage (leaving him with the mind of a three-year-old) while Brown “was eventually sentenced to five years imprisonment and dismissed from the armed forces”. Over a half dozen “others were charged” yet most received reprimands or were acquitted in court martials.

The charges against Matchee were dropped in September of 2008 once the Saskatchewan Review Board determined it “reported there have been no incidents constituting a risk since Matchee’s release”.

The Canadian government, in 1996, created the Commission of Inquiry into the Deployment of Canadian Forces to Somalia, which, while it predominantly explored the events leading to and regarding Arone’s death, also “quickly uncovered evidence of mass hazing of soldiers and other troubling incidents, as well as a brazen coverup by senior officials at National Defence Headquarters … [resulting] in the chief of the defence staff resigning after being implicated in manipulating documents for public release two years earlier, and a sweeping set of reforms to the military”. However, only sixteen months after the inquiry’s creation, the Canadian government under Liberal Prime Minister Jean Chrétien “abruptly shut the hearings down at the end of 1996” demanding a final report by 1997, rationalizing that “Canadians had lost interest in the Somalia affair”.

Conclusion

From a larger standpoint, this event significantly changed the way in which the Canadian people and government thought about, engaged with, and utilized elite military forces and also worked in peacekeeping operations.

The Washington Post, reporting on the conviction of Brown in 1994, stated, “[the event] has dealt a blow to Canada’s image as the postwar era’s preeminent international peacekeeper, and to Canadians’ self-image as a people naturally adept at mediating and stabilizing foreign conflicts”.

David Bercuson, a political and military history professor of history at the University of Calgary, was quoted as saying the Somalia Affair was “the darkest era in the history of the Canadian military” since the Second World War. To this day, Canadian’s views of their military’s involvement in peacekeeping or direct action operations are colored substantially by their past conduct in Somalia exactly thirty years ago.

Every military has skeletons within its history. This is not an excuse for such behaviour but rather highlights an important and essential need for accountability and proper oversight of military operations. Furthermore, perhaps even more importantly, this event serves as a reminder to further tamp down extremism and racism within the Armed Forces. This event was highly racially motivated, with the CAR soldiers involved using racially charged language during the event but also while on patrol and peacekeeping missions.

This event further revealed substantial issues within the Canadian military justice system and past instances of abuses, violence, harassment, and prejudice in relation to race and gender, in many ways similar to the current state of the United States Armed Forces, which has itself been dealing with sexual assault and harassment, racism, and political extremism/violence within their own ranks. Exploring how the Canadian military and governmental departments had dealt with the ramifications of such actions in their own force back in the late 1990s and early 2000s (in spite of its apparent shortcomings) could prove beneficial to American defence policymakers and general officers.

No military force or national defence apparatus will ever be perfect or free of the internal, societal problems from which its’ ranks are made of. However, there are ways by which an armed force can better insulate itself from the negative, persistent societal changes that can harm an operation abroad or domestically.

By properly educating their soldiers, consistently reminding them of their duty and ethos, performing proper background checks in search of extremist or racist behaviour/rhetoric, and having a strong, personnel-focused leadership mentality in all officers, a military force can be able to stave off many of these negative behaviours of racism and extremism (and more criminal acts) before they even take place, ensuring for the most strong and able national defence.